Revolutionary Corps, a portrait of Colleen Doran and Emil Ferris by Valentina Griner: https://www.fumettologica.it/2021/04/colleen-doran-emil-ferris/

Thursday, April 15, 2021 at 18:00 for the "Women in Comics" cycle, the meeting "Revolutionary bodies and women who draw them" will be held, between Emil Ferris, Colleen Doran (from the USA) and Sara Pichelli (from Italy), moderated by Riccardo Corbò. Live on Zoom and on the ARF Facebook page and COMICON . The event anticipates the Women in Comics exhibition to be held in Rome.

The history of comics is also the story of how the representation of the body has evolved. In the visual story, there is not only the need to give shape to anatomy in a technical sense. The physicality of the characters is as important as their acting and, on a further level, the body is the object of the story itself, it is a representation, a sign of what is being told.

The realistic-grotesque ones of Andrea Pazienza, the hypertrophic ones of Simon Bisley, the big nose women of Claire Bretécher, the scribbled bodies of Maicol and Mirco are “talking” bodies. And so on.

From this point of view, two authors who would seem light years away from each other, by debut, career, style, and training, are united by their research in the representation of the body, not only as the subject of the story but as the object of the story itself.

Colleen Doran and Emil Ferris, first of all, share the period of birth, the very early sixties in America, Doran in the New York of the Stonewall riots (considered the birth of the gay liberation movement), and Ferris in the Chicago of racial tensions and Martin's Freedom Movement Luther King Junior. Both approached art and drawing as a child, Doran with her first self-production at fifteen and Ferris with comics who, blocked by a bust due to a malformation in the spine, designs for classmates.

While for Emil Ferris drawing is a relief and the relationship with the disease will be central in all her production, for Colleen Doran it is a way to free the worlds in her head and to enter professionally in the comic, still a teenager, after a debut. in the small press (a sector that it will never completely abandon, fertile ground for artists who want to create without the constraints of publishers and circulation).

In the early eighties, Colleen Doran stands out for a very wide-ranging story, which she writes and draws entirely by herself. A Distant Soil, “epic sci-fi opera” starring a young woman with psychic powers in a futuristic world halfway between science fiction and medieval epic novel. The unique author, the mix of genres, and the fact that queer themes are addressed, makes it a totally innovative product, so much so that it first attracted the interest of Warp Graphics, its first publisher, and then of others up to Image Comics. In fact, the saga has not yet ended even if, after many periodic releases, Doran has announced that she wants to write an ending shortly.

Following the evolution of comics over the years, the growing attention to the study of the graphic construction of the table and the psychological and physical characterization of its characters is evident. Colleen Doran is talented and productive enough to drop out of school very early due to the sheer amount of commissions and deadlines involved.

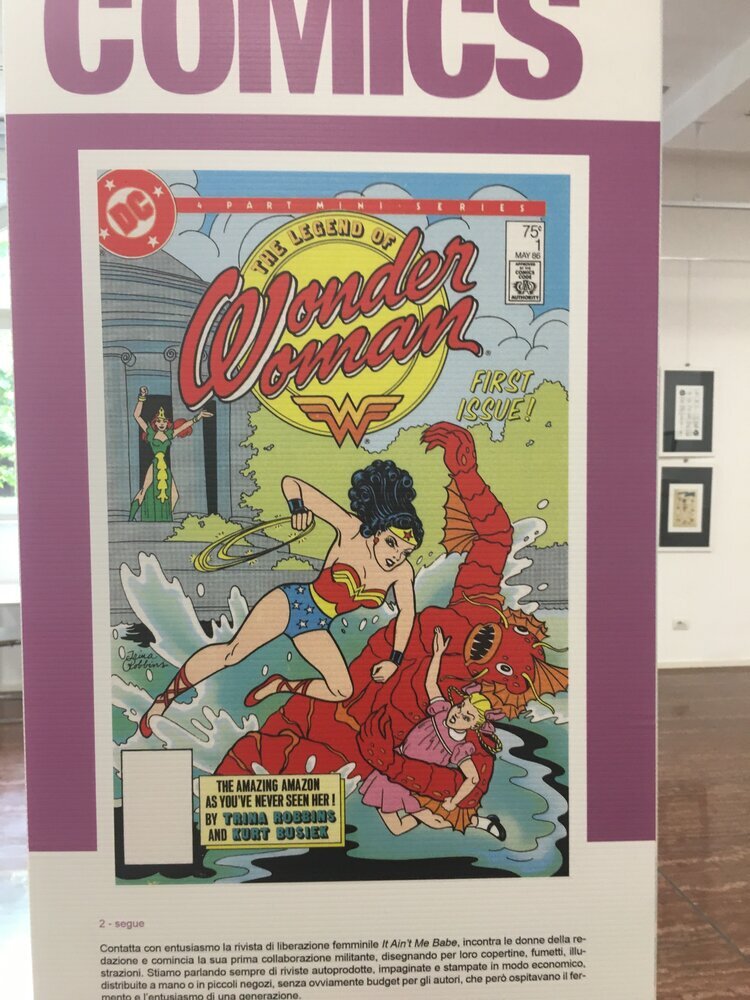

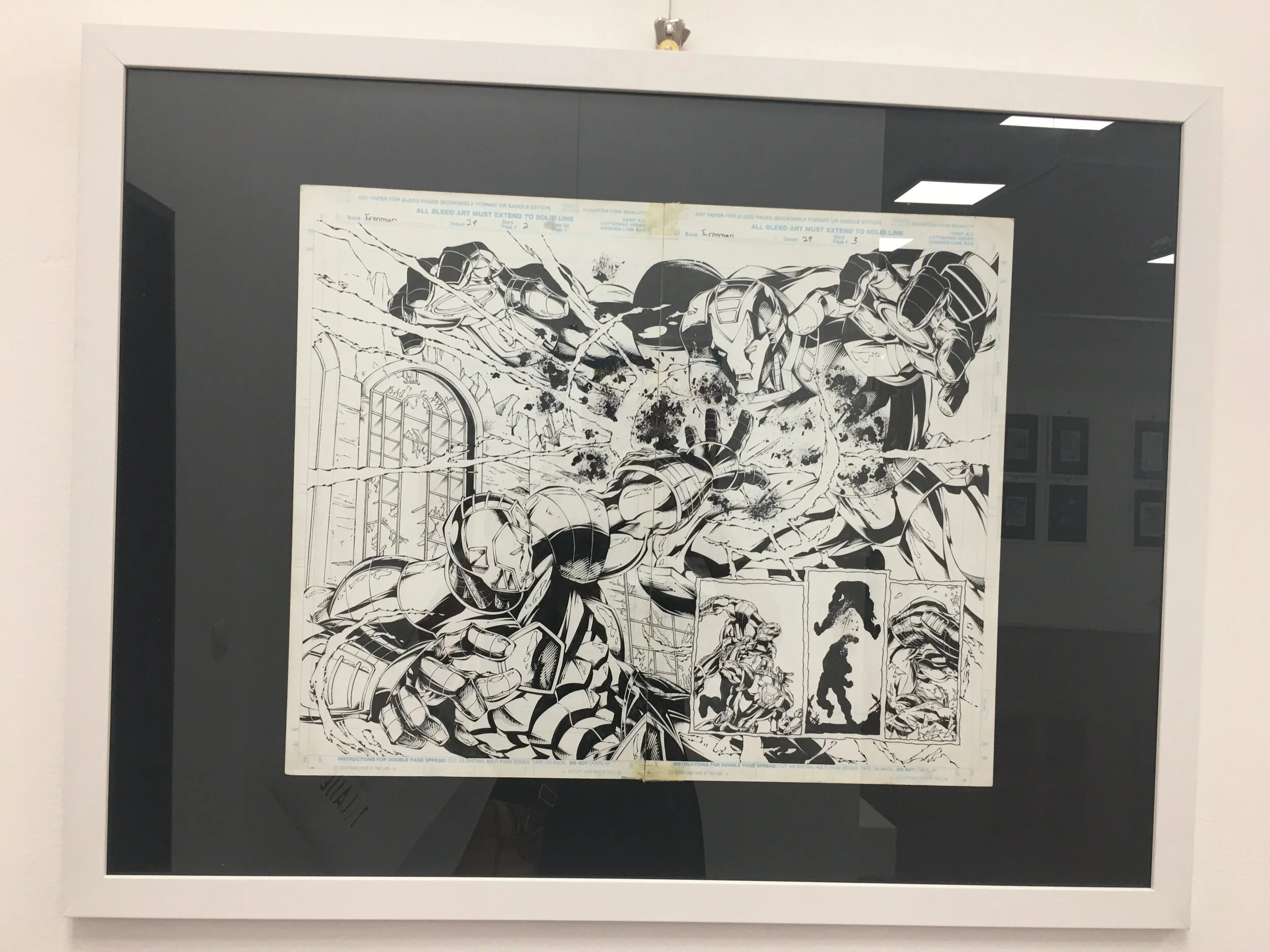

In 1985, cartoonist Keith Giffen realizes her skills and introduces her to DC Comics and her first professional comics work. Among the titles to which he dedicates herself, Teen Titans and Wonder Woman. Almost immediately, Marvel Comics also notes her and entrusts her with several issues of important titles such as The Guardians of the Galaxy, The Silver Surfer, Captain America, Amazing Spider-Man, X-Men ... also works closely with Stan Lee for the marketing sector of Marvel: her personal acquaintance relationship will lead her to design in 2015 the celebratory volume Amazing Fantastic Incredible Stan Lee, written by Lee himself and Peter David.

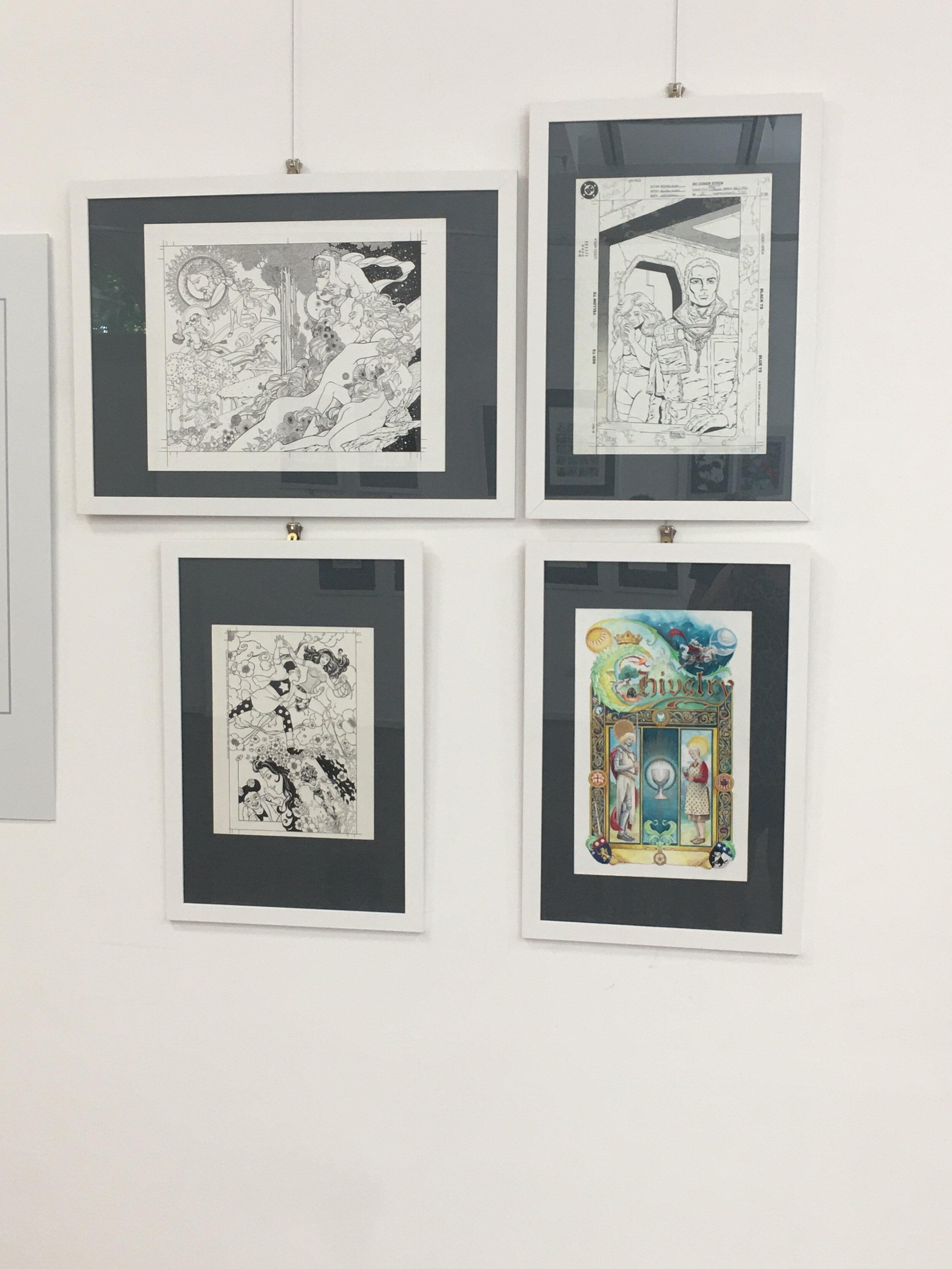

Alongside the rich production on the most mainstream titles, there are her authorial works, in which one can indulge freely in his artistic research, even on the representation of the body.

Over the years she collaborated with some of the most important authors of the period, protagonists of the British Invasion which strongly influenced, from the mid-eighties and then into the nineties, the level and tone of mainstream superhero comics, science fiction, and American fantasy.

With Neil Gaiman, for example, she worked on Sandman, illustrating the cycles A Game of You and Dream Country. With Warren Ellis she worked on Transmetropolitan (in a one-shot collateral volume, I Hate It Here ) and above all on Orbiter .

Orbiter, released in 2003 with Vertigo, seems almost sewn by Ellis on the Doran stretch. The crew of a ten-year missing space shuttle suddenly reappears, but all members are catatonic and their journey holds some kind of mystery. In particular, part of the aircraft became organic. It is not strange that Ellis has chosen precisely the physicality of the unconventional characters of Colleen Doran, to make this component uncanny.

Doran is now in her forties. She and Emil Ferris are almost the same age and just at the age of forty the life of Ferris, already not easy, changes forever.

Emil Ferris as a child, forced into an orthopedic corset, entertains classmates in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago with her drawings. Daughter of two artists, Eleanor Spiess, symbolist painter, and Mike Ferris, designer and illustrator, Emil would like to follow in the footsteps of her father, who designs toys and even pinball machines. However, pinball machines are male territory and these commissions will remain closed to her. She has motor problems and the doctors offer her a painful future and a fairly short life. She, fond of monsters, of Filmland's Famous Monster magazine, of EC comics, wonders if the condition of a monster, in the sense of an outsider, of a person on the margins, is somehow close to her.

She also leaves school early, does tasks that allow her financial survival, and meanwhile continues to work as a freelance illustrator. Pregnant with a child at thirty-four, she never stops managing multiple jobs at the same time.

Exactly on the day of her 40th birthday, the banal bite of a mosquito transmits a potentially lethal disease, caused by the West Nile virus.

She wakes up after nearly a month in a coma, has a six-year-old daughter to care for, and paralysis in most of her body. The doctors throw what looks like yet another curse, she won't walk anymore. She does not give up and begins to draw what will be, fifteen years later, her debut graphic novel. She draws it with a ballpoint pen on a notebook and gets help from her daughter. She finishes college, a woman in a wheelchair in the midst of droves of twenty-year-olds full of hormones and life.

She makes drawing her physiotherapy. What she could no longer do, maintain control of his realistic hatching style, the son of classical and modern art studies and visits with her brother and parents to the Art Institute of Chicago, gradually returns to emerge on paper. It will take years to finish her first book and dozens of publishers will reject it, until she meets Fantagraphics Books.

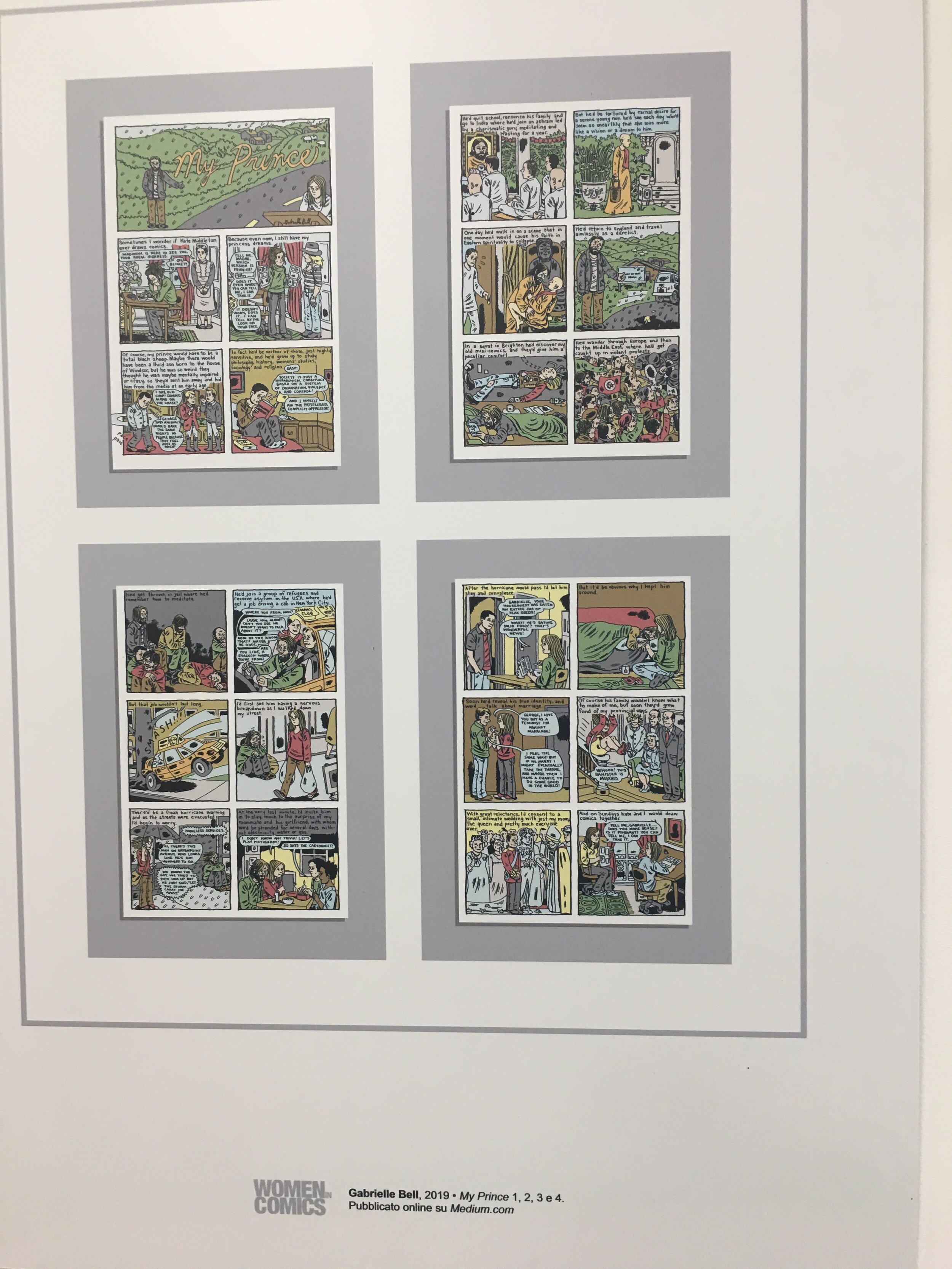

My Favorite Thing is Monsters (in Italy: My favorite thing are the monsters , Bao Publishing, 2018) is the diary of the small Karen Reyes, ten-year-old girl from a multiethnic family, just like that of Ferris.

Little Karen is portrayed as a werewolf girl who, committed to living the life of the neighborhood, runs into a murder; her neighbor, a Holocaust survivor, is shot and killed and she decides to investigate. The book comes out with the same lined layout of his notebook and without the cage in the table, like a diary (the text is very rich) illustrated with drawings and comics. The influences on the style of Ferris are many and all deliberately recognizable and explicit: from Daumier to Goya, to get to the illustrated books (in particular the complete work by Dickens of the publisher Collier) and to her masters in the comic field, Art Spiegelman, Robert Crumb, Alison Bechdel.

A narrative thread unites her tormented life, the hand rehabilitated by the exercise (her outlined style is the result of a patient and hypnotic work) and the bodies she draws, characterized by bearing the signs of their history; in the book coexist embodied works of art, funerary statues that come to life, monsters that are grotesque and funny and truly monstrous and dangerous human beings.

For Ferris, the monster is the symbol of something that differs from the commonly accepted norm: a sick child first, then a girl attracted to other women and with a life on the fringes, the monster is the one she hopes to transform into in order not to have to define herself. necessarily in a precise way, to escape from a sick body, or even, kissed by a vampire, to become a body that overcomes death.

As Emil Ferris struggles to get her book published around 2015, Colleen Doran is teaming up with yet another sacred monster, Alan Moore. Emil tells the story of the wolf-girl, Colleen illustrates a webcomic experiment on a portal that Moore called Electricomics, works that will never be printed and born for the web.

Also in this case the story is about a child, one of the most famous of the protagonists of the comics, Little Nemo. In Moore and Doran's version, the delicate turn-of-the-century baby wakes up in the devastated and disenchanted body of the adult Big Nemo, who definitely no longer lives in Slumberland.

A good year goes by, and My Favorite Thing is Monsters has gone to press. Or rather, it was sent to print abroad because many publishing houses decentralize the work for large runs, to lower costs. While the freighter carrying the book run is crossing the Panama Canal, the Chinese transport company goes bankrupt and the freighter is seized for months. For those who have an emotional relationship with books, it is alienating to think how, in their physicality, they are goods, packages, packages, and boxes, and that they can be victims of accidents and upheavals. Like those who continue to haunt Ferris' life and whom she faces with an enviable willpower.

When it is finally published, the reception of the book is surprising (it will come out in two volumes, being about 700 pages): it wins two Ignatz Awards and three Eisner Awards; is nominated for a Hugo Award as "Best Graphic Story" in 2018, wins the Fauve D'Or at the Angoulême International Comics Festival, and the Gran Guinigi 2018 for the best graphic novel at Lucca Comics and Games. In recent news, Ferris has won a fellowship at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. They are all important and prestigious awards, but above all the success is with the public.

In 2019, Colleen Doran returns to collaborate with Neil Gaiman who, like Warren Ellis, appreciates his sign and his ability to adapt to stories: together they work on the reinterpretation of a timeless fairy tale, Snow White, which will be released with the title of Snow, Glass , Apples . The story starts from the stepmother's point of view.

To tell this immortal and classic story, Colleen Doran does a very thorough stylistic research on Harry Clarke, illustrator and glass engraver, active in Ireland between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Her style, reminiscent of that of a darker and more tragic Aubrey Beardsley, fascinates her very much and when she discovers that Neil Gaiman has an original, she runs to England to study it from life, especially in the use of color.

By a coincidence of fate, or because the tone of the story marries in both cases with this livid atmosphere, the result will be a color palette very similar to that of My Favorite Thing is Monsters.

As she has already done, and as Emil Ferris has also chosen in her book, Colleen Doran frees herself completely from the cage and chooses to mark the time of the story through the composition of the table; the bodies, the costumes, the environments become decorative details but at the service of the story.

The life of the two authors also meets on a point to be touched with a lot of respect, given that they themselves have decided to talk about it only partially; the issue of harassment.

Doran hinted at this during the early stages of the #MeToo movement, stating that she cannot talk about the situation she experienced as a young woman due to an NDA contract, a type of agreement that provides for the non-disclosure of certain confidential information. She hinted that she had experienced situations of abuse during a working relationship when she was young and still inexperienced. Emil Ferris recounted in more detail what happened to her as a child and the abuses by an acquaintance of relatives, but she still decided not to make it a central topic in the description of her artistic growth and in her biography.

Similarly, even if for Ferris this characteristic is much more evident, the idea of drawing as therapy ends up by combining their two sensibilities. It is Colleen Doran who speaks in these terms interviewed by The Comics Journal about the style she took from that of Harry Clarke, but she could not better tell what Emil Ferris herself describes:

“[After studying his working method], I wondered how much of that approach was meditative or therapeutic for him. That kind of work puts you in an incredible zen state. It sounds strange, but looking back on Clarke's health problems, I was wondering how much of that approach was a reaction to her infirmity. As a person with chronic health problems, I pay close attention to which arts activities consume you and which are invigorating. You spend hours every day on those little details and want to take your arm off. But in the end, it is hypnotic. I bet drawing those things made him feel better. It made me feel better. '