Fumettologica - Robbins, Escobar, Martinez, Flowers, Doran, and Ferris

/In May and June 2021, the ARF comics festival and the US Embassy organized a series of zoom artist talks in conjunction with Women in Comics at the Palazzo Merulana in Rome. The Italian comics magazine Fumettologica published articles on the work of each artist by Italian reviewers. These articles were also posted in the gallery for museum visitors to read while looking at the exhibit.

This is the best translation I can get using auto-translate. I have left reference links and bold/italic highlighting as they were. These articles included many images. I’ve provided the original link so you can see them.

Trinidad Escobar, story of the girl born from a typhoon by Valentina Griner https://www.fumettologica.it/2021/06/trinidad-escobar-fumetti/

Thursday 10 June 2021 at 18:00 for the cycle "Women in Comics" will be held the meeting "Drawing Power - Violence and the relationship between gender and identity in comics", between Trinidad Escobar (from the USA) and Rita Petruccioli ( from Italy), moderated by Casa delle Donne Lucha y Siesta. Live on Zoom and on the ARF Facebook page and COMICON. The event accompanies the Women in Comics exhibition held on these days in Rome.

One detail unites the stories of different people who have lived the experience of being adopted: the fact of asking sooner or later who they look like, who they are similar to. The question arises first from an aesthetic question to the traits of those who resemble mine, and then extends to deeper questions; not only who we are like, but also who we are similar as a story, in relation to emotions, to the ability to interact with the world; which people inhabit a history similar to ours.

Often we do not stop to think about how many elements determine an identity: a language, a place of birth, affections, a name, the names of things, a date of birth, a cultural education, an environment. If all this were taken from us very early, would it disappear forever? And above all, could we feel supporting actors or even extras of a story that is not ours, and would we like to have the opportunity to tell us a different one?

Trinidad Escobar starts with similar questions when he decides to draw his book Crushed, published as the final thesis of his studies at the Californian College of The Art (where he currently teaches). He temporarily abandons fiction to tell his comic biography, finding in this new narrative key a way to tackle the great theme of identity, whose construction (and deconstruction) is the journey that sees us all as protagonists.

If the construction of identity is a process that involves everyone, some biographies are more illuminating than others, when the protagonists find themselves having to face particularly intense situations, as happened to Escobar: hers is not just the narration of an origin and of a rediscovered country (the Philippines where she was born), but unfortunately also that of discrimination linked to minorities, and the terrible issue of child abuse. His luck was that of knowing a very powerful, universal and adaptable storytelling tool, the comic. When one's need to use narrative as an expressive means is also combined with the awareness of facing a trauma, the comic becomes not only an exploratory and didactic means but also a powerful therapeutic act.

Born in Bataan, Philippines, Trinidad Escobar was given up for adoption at three months and brought to America, in Milpitas, California, by adoptive parents (themselves Americans of Filipino origin) who had just lost the chance to adopt another child. Filipino, died of malnutrition. Little Trinidad is given the name (Nicole) and personal data (including birthday) of the child who passed away, to facilitate the paperwork.

At the age of eighteen, she has the opportunity for the first time to get to know her biological family, also thanks to the permission of the adoptive parents who could have opposed the request of the other family. Ten years later, on their honeymoon, Trinidad returns to visit her parents and numerous brothers and sisters. The husband is Filipino and grew up in the Philippines and can therefore act as an interpreter, while at the same time representing a bridge and a filter to his parents and his native language.

In the journey (at the center of her book Crushed ) she is also accompanied by presences to which she embodies with the drawing: her child self, a demonic figure that torments her, a siren who announces her birth during a terrible typhoon in 1986, an aswang (a vampire demon); metaphors of her own evils, of the traumas she experienced as a child.

The author uses elements taken from the folklore of tribal magic, traditional tales, in a path that combines the search for roots with a holistic vision of life, where nature, art, culture, come together to create a bridge, to explain why an imposed identity is an identity that is actually deprived of its potential. The presence of magic, taken from the traditions of both countries, is also a constant in his other works, ranging from poetry to music, from masonry to erotic stories.

The comic allows Trinidad Escobar, as she herself declares when talking about her relationship with her art students, to explore complex themes, giving them access to a very wide audience, thanks to the facilitation of the visual tool. His synthetic style, with a predilection for black and white or duotone, favors a smooth reading and the introduction of graphic elements that integrate the sense of the story, as well as the magical and supernatural presences used in a metaphorical sense.

During her career, she has produced several works of graphic journalism and comics that address social issues, all very close and dear to her: the presence of different ethnic groups in publishing, so that they are a stimulus for the boys and girls who grow up inside. of minorities; the denunciation of inequalities; the theme of colonialism.

In its short story The Colonial Roots of Cheese Pimiento (written by Malaka Gharib and readable on the Escobar website ), for example, tells how an industrial product was introduced in the Philippines during the colonial period and became a national food, starting from a topic light and fun, the snack that her relatives prepared for her as a child.

Her biography is an incredible crossroads of almost all the issues that globalization has made central: coexistence between peoples, gender violence and violence against the weakest, to arrive at international adoption and issues related to intersectional activism. Trinidad Escobar has declared herself queer and associates this umpteenth complexity with the other identity issues that have enriched her life, albeit the result of extremely traumatic experiences. As an author she deserves great merit, that of telling and drawing lightly and with competence, with the grace of looking for a common thread of events, focusing on the desire to study and deepen what we are talking about.

The title of her biography, Crushed , is the translation of the etymology of the surname of the family of origin (Dorognas). It could be further translated (underlining that at the third level of translation the origin of the word is certainly betrayed) as "crushed, torn to pieces". It is the condition that the author finds herself living crushed by the weight of many fears, her insecurities as an "abandoned" daughter and unfortunately those of her adoptive mother, whose story we do not know, if not evoked with a certain understandable modesty; the story of yet another person straddling cultures (American and Filipino) who subjects his daughter to abuses, echoing, perhaps, most likely, those she herself suffered.

Many of Trinidad Escobar's short stories can be read for free on his website, trinidadescobar.com . Her works are the sign of a cultural richness, the stories of a part of the world that has still remained unheard today. Escobar enriches them with the desire to continue studying the encounter, between peoples, between languages, between people, and between languages, poetry, comics, art.

His comics have been featured in newspapers such as The Brooklyn Review and The New Yorker , and he has participated in several major anthologies related to activism, such as Drawing Power (edited by Diane Noomin, Eisner and Ignatz award-winning book) and Be Gay , Do Comics (IDW).

Anti-racism, feminism and intersectionality in comics: Alitha Martinez and Ebony Flowers by Mara Famularo: https://www.fumettologica.it/2021/05/alitha-martinez-ebony-flowers-fumetti/

On Thursday 13 May 2021 at 18:00 for the "Women in Comics" cycle, the "Balloon Intersectional" meeting will be held, between Alitha Martinez, Ebony Flowers (from the USA), Fumettibrutti and Elisa Macellari (from Italy), moderated by Sarah Di Nella for the Bande des Femmes festival. Live on Zoom and on the ARF Facebook pages and COMICON. The event anticipates the Women in Comics exhibition to be held in Rome.

By intersectionality we mean the superimposition of different social identities and the resulting forms of discrimination. The concept was formulated by activist Kimberlé W. Crenshaw about the forms of oppression, and even insults, reserved for women of color (which often indistinctively combine sexism and racism) but in reality, it is applicable in many other situations in a complex and globalized reality. The element of intersectionality has broadened the feminist perspective by enriching it with the demands of anti-racist and transfeminist movements, and with good reason: if discrimination is intersectional, intersectional can and must be the way in which the struggle for rights is carried out.

One way to combat discrimination is to deconstruct stereotypes and clichés that negatively affect the mentality of a community. This implies rethinking the concepts of individuality and identity, admitting that they do not have rigid forms but rather elusive definitions. Any territory, personal or professional, can turn into a scenario suitable for this revolution, including comics of course.

Alitha Martinez and Ebony Flowers made their comics debut twenty years later. Martinez has a long career in mainstream comics as an illustrator of Iron Man, Fantastic Four, Batgirl, Voltron, and X-Men, while Ebony Flowers, author of Hot Comb, is an independent comic book voice with an ethnographic background.

Martinez and Flowers have different personalities, inclinations, and goals, but they are both American women of color who have made space in the world of comics by carrying forward, each in their own way, feminist and anti-racist demands, breaking through an environment that is not very sensitive to those contents. and making comics a ground on which to discuss diversity and expand the forms of representation.

"I'm certainly not a comic star, " says Alitha Martinez of herself despite her twenty-year career as an illustrator for major American comic book publishers, from Marvel to DC Comics to Image and Archie Comics. Behind this statement there is certainly a work ethic that pays attention to the point, neglecting ( perhaps too much ) sequins and spotlights, but also a clear awareness of the internal dynamics of the world of comics and its transformations from the nineties to today and a certain tenacity in wanting to look beyond the preconceived schemes, without fixing oneself in a position in which many others would gladly bask.

Martinez was born in New York to a black family originally from Honduras and Curaçao who did not have a high regard for comics. Used to hiding her love for superheroes, in the 90s she enrolled in the School of Visual Art, discovering that she was the only girl in the entire department dedicated to comics. A situation that often made her uncomfortable and, thinking in retrospect, probably determined her shy approach to the world of comics: working with her head down, on the sidelines, trying to give the best of herself without ever attracting attention.

During a convention she has the opportunity to show her drawings to Joe Quesada , who would become Marvel's Editor-in-Chief in a few years. Quesada offers her to become his ghost, and so Martinez begins working as an assistant until in 1999 she is finally credited as a designer for Cable Annual # 1.

But even the House of Ideas is not exactly a girl-friendly environment: Martinez has only one female colleague, Amanda Conner. As she tells in an interview on Black Girl Nerds, there was a "mansplaining that would drive anyone crazy" and it was customary to keep women in the shadows to draw and ink, nullifying any desire to write or simply to bring forward ideas personal.

Martinez works hard, collecting a significant number of titles and drawing Iron Man and the Fantastic Four among others. In the meantime, the world of comics undergoes several changes, the number of women who choose to work in superhero titles increases and slowly the idea that it is a woman who scripts no longer appears so crazy. In 2012, just before Amanda Conner gets to work on Harley Quinn, Martinez works on DC Comics for Gail Simone's Batgirl, and with the author creates Knightfall, a supervillain who becomes such after witnessing helplessly the massacre of her family by her boyfriend - a character that seems a tribute to the project with which Simone had come to the fore years before, Women in refrigerators.

Working on superhero comics, Martinez perfected herself in the design of athletic bodies capable of performing all sorts of stunts and in the rendering of excited and lively action sequences. But she also develops two elements that on closer inspection constitute her peculiarity: the attention to the emotional sphere of the characters, represented through the expressions of the faces, the looks and the small gestures that build relationships between them, and the ability to adapt the inking, sharper or dirtier, to the tone and sense of the story. For this to be possible, the author can only begin by carefully reading the script.

As she prepares for Black Panther's launch in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Martinez is working on the Black Panther: World of Wakanda miniseries. At the center of the story are the Dora Milaje, the warriors who have the task of protecting the royal family of Wakanda . Created by Christopher Priest for a 1998 issue of Black Panther, they looked very different (and Martinez remembers it well and with some embarrassment since she had worked as a background assistant on that book): a kind of Bond girl, very sexy, armed to the teeth but in skimpy red dresses, smooth hair and stiletto heels. In short, a look that is hardly compatible with the role of T'Challa's bodyguards.

In contrast, World of Wakanda's Dora Milaje sport hairstyles and tattoos that are reminiscent of African tribal traditions, and while they don't disdain the miniskirt when they are on the loose in an American metropolis, if they train or perform their duty they wear equipment. convenient and practical.

The World of Wakanda series centers on two warriors, Aneka, captain of the Dora Milaje and very respectful of her duties, and the young recruit Ayo, talented and insolent. A deep love is born between the two that forces Aneka to question herself , her integrity as a captain and also her loyalty to the royal family, in a situation that sees Wakanda threatened by Namor and T'Challa too taken by the Avengers to solve the problems of the kingdom.

Martinez draws on the scripts of Roxane Gay and Yona Harvey. Adding Afua Richardson to the team, who makes some covers, World of Wakanda is the first series entirely made by women of color and in 2018 wins the Eisner Award, as well as receiving the GLAAD Media Award for sensitivity towards LGBT issues.

After the victory at the Eisners and the great success of the cinematic Black Panther, in many interviews Martinez is called into question to have her say on the representation of the African American and Afro-Latina community in mainstream comics. Showing great intelligence and sensitivity, Martinez is very careful not to simplify the matter and to reject any label that risks flattening the perspective of readers and readers but also the meaning of her work. “Perhaps the point is not so much [to represent] diversity in itself - she declares - as to create a more realistic form of reflection. The books we are most attached to are those that have a point of contact with our real world, and in our real-world, there is a magnificent mix of everything and everyone, there is never a single point of view”.

At the same time, Martinez recalls that if we have to take as a positive sign the fact that more women work in comics than in the 1990s, it is also true that most of the authors work in independent publishing, few remain professionals in mainstream publishing and very few those who are entrusted with leading characters and titles. Therefore, the variety of points of view that women could give and which would contribute more quickly to deconstruct certain stereotypes of representation is still lacking in the superhero comics. On the other hand, it would be an aberration to consider the work of an Afro-Latina woman as valid and interesting only for female readers, or for members of the Afro-Latina community: the real step forward is to recognize whoever creates a story "as an artist who has every right to be so as a human being".

Over time, the superhero comic has crystallized rules that cannot be easily circumvented. That's why, thanks to the ability to grind an impressive amount of work, Martinez has always carried out even less mainistream projects . The best known example is the Omni miniseries, written by Devin Grayson, published since 2019 by Humanoids and centered on a female doctor of color who works for Doctors Without Borders and has the ability to think faster than normal, a character that contradicts the stereotype of blacks as a disadvantaged and poorly educated social category.

Then there are the real self-productions, published starting from 2008 with her Ariotstorm label (renamed after her old nickname). Contrary to what we would expect from such a famous author, Martinez hardly frequents social media and does not use her notoriety to sell personal works online, preferring to do the old-fashioned way, that is, holding small stands at conventions in person so that, according to her, talking will face to face with the readers is the way she knows to make comics.

The first Ariotstorm self-production is the Yumi and Ever series, for which Martinez had to learn at great speed to color, layout, write and carry out all those parts of the work that are generally not her competence. It is an adventurous story where there are teen superheroes of various ethnic backgrounds, a supervillain, and catastrophic scenes of great impact, such as the destruction of Tokyo. The series is characterized by the sequence without dialogues and words that occupies the entire first issue , a deliberate choice to invite readers to dwell on the incipit of the story longer than they would read the texts in the balloons.

The second self-production, still in progress, is Foreign: Modern Savages, 147 Days, a SCI-FI story about a community that lives in space but hopes to return to Earth. Developed from a personal passion for the genre and from ideas and characters elaborated in his early experiments as a teenager, which became reality at the request and encouragement of his teenage son, Foreign is the project Martinez talks about most fondly. After all, it is the realization of an idea that she has been carrying with her for years but perhaps, and also, it is the one that comes closest to the realization of the dream of a lifetime: "It is said that there are no black science fiction writers, who cannot live by doing just that, yet they do. This is a new frontier to be conquered. That's where I'd like to get to. We'll see".

"To be honest, mainstream comics aren't really my field," admits Ebony Flowers, who actually came to comics through a decidedly unusual path. After studying physical anthropology in college, Flowers enrolled at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. There she meets Lynda Barry, author of unique comics like The Good Times are Killing Me and One! Hundred! Demons! and recently hired as a teacher of interdisciplinary creativity. Animator of the Image Lab, a research space oriented towards science, education, and art, Barry holds workshops that combine drawing and writing exercises, experimenting with useful methods to defuse performance anxiety and encourage confidence in one's means of expression, in a teaching activity so passionate that it deserves the prestigious Genius Grant awarded to creative personalities.

“Lynda taught me how to make comics. And he also taught me to be a curious person,” says Flowers honestly, who finds in Barry a point of reference and a mentor from whom she takes up the idea of comics as a freely creative means of expression. Become her assistant and an integral part of a group of people who gravitate around the Image Lab and constantly exercise their creativity, encouraging each other and sharing their discoveries with others. This work also represents the fulcrum of her final thesis in Curriculum and Instruction, where she tells and analyzes some workshops in which university students and children played and drew together, allowing the creation and passage of knowledge between the parties.

For Flowers, the most coherent solution is to write the thesis in comics, that is by combining a textual dissertation with a designed part capable of transmitting research data in a less boring and more understandable way (with the result that not only the speakers, but also their children start reading it). Distinguishing herself for this innovative and accurate work, in addition to obtaining her PhD, in 2017 Flowers won the Rona Jeffe Award, a substantial scholarship that allows her to devote herself to research and writing.

Flowers therefore approaches comics as a creative exercise and then transforms it into a useful tool for sharing ethnographic research. It is only after these two steps that she comes to use comics in a more traditional way, that is, as a means capable of telling stories. And the stories that interest her are those that tickle her sensitivity as an ethnographer, made up of attention to detail and imagination, awareness of her own experience, and of the multisensory dimension of which experiences and memories are made.

It is from this spirit that Hot Comb was born, published by Drawn & Quarterly in 2019. The volume collects several short stories, some of autobiographical inspiration, which have as their theme the relationship of the protagonists, girls and black women, with their hair - and in fact, the title refers to the electric comb that black women use to straighten them.

“Hair - explains Flowers - is an important aspect of our life. Afro hair speaks of their time together. They express intimacy. They refer to pop culture. They are part of a personal story shared with a community. The issue of afro hair, in America as in the rest of the world, is intertwined with the legacy of white supremacy, social classes, inequality, and capitalism. By choosing to tell stories about afro hair, I knew I was also intercepting many other aspects of black life.”

The history of black hair is political, but in Hot Comb the political element never slips into proclamation or stereotype, because the focus is always on people observed in their context with the acuteness of an ethnographer but portrayed in their own complexity with the sensitivity of an artist.

There is also the ironic element: between one story and another, Flowers inserts advertisements for fake hair products, a satire of the conditioning that the consumer society imposes on women of color but also an invitation to emancipate themselves and accept themselves for this. that is it.

The graphic style of Hot Comb is the coherent development of one of Barry's fundamental teachings, the ability to "discover writing in drawing and drawing in writing": black and white drawings are highly expressive, and through a deliberately naive stroke they naturally blend with the texts, enclosed in balloons or breaking free in the cartoon. The rigid distribution of the table in a grid of regular vignettes does not dampen the impression that figures and words flow indistinctly from a single inspiration, according to a working method in which writing and drawing actually spring together as in the creative exercises learned at the Image Lab.

Furthermore, the wild and spontaneous sign is by no means devoid of accuracy: for example, Flowers manages to portray afro curls in their variety, including a real tutorial on how to create a hairstyle in a story.

Hot Comb achieves great success and also numerous awards, including Eisner and Ignatz 2020 , and Flowers becomes one of the most interesting female voices in independent comics, so much so that she participates in the anthology born on the wave of #MeToo, Drawing Power: Women's Stories of Sexual Violence, Harassment, and Survival.

With this debut Flowers has made several revolutions. She explored the communicative potential of comics by identifying a graphic formula capable of preserving the immediacy of the creative process from which it was born, and managed to evoke characters in which an entire community can reflect itself, deconstructing many stereotypes. All while remaining faithful to her personal vocation: "My hope in making comics is to tell stories that others would not notice or which perhaps they would not give weight, and make sure that they notice things they had left out."

Revolutionary Corps, a portrait of Colleen Doran and Emil Ferris by Valentina Griner: https://www.fumettologica.it/2021/04/colleen-doran-emil-ferris/

Thursday, April 15, 2021 at 18:00 for the "Women in Comics" cycle, the meeting "Revolutionary bodies and women who draw them" will be held, between Emil Ferris, Colleen Doran (from the USA) and Sara Pichelli (from Italy), moderated by Riccardo Corbò. Live on Zoom and on the ARF Facebook page and COMICON . The event anticipates the Women in Comics exhibition to be held in Rome.

The history of comics is also the story of how the representation of the body has evolved. In the visual story, there is not only the need to give shape to anatomy in a technical sense. The physicality of the characters is as important as their acting and, on a further level, the body is the object of the story itself, it is a representation, a sign of what is being told.

The realistic-grotesque ones of Andrea Pazienza, the hypertrophic ones of Simon Bisley, the big nose women of Claire Bretécher, the scribbled bodies of Maicol and Mirco are “talking” bodies. And so on.

From this point of view, two authors who would seem light years away from each other, by debut, career, style, and training, are united by their research in the representation of the body, not only as the subject of the story but as the object of the story itself.

Colleen Doran and Emil Ferris, first of all, share the period of birth, the very early sixties in America, Doran in the New York of the Stonewall riots (considered the birth of the gay liberation movement), and Ferris in the Chicago of racial tensions and Martin's Freedom Movement Luther King Junior. Both approached art and drawing as a child, Doran with her first self-production at fifteen and Ferris with comics who, blocked by a bust due to a malformation in the spine, designs for classmates.

While for Emil Ferris drawing is a relief and the relationship with the disease will be central in all her production, for Colleen Doran it is a way to free the worlds in her head and to enter professionally in the comic, still a teenager, after a debut. in the small press (a sector that it will never completely abandon, fertile ground for artists who want to create without the constraints of publishers and circulation).

In the early eighties, Colleen Doran stands out for a very wide-ranging story, which she writes and draws entirely by herself. A Distant Soil, “epic sci-fi opera” starring a young woman with psychic powers in a futuristic world halfway between science fiction and medieval epic novel. The unique author, the mix of genres, and the fact that queer themes are addressed, makes it a totally innovative product, so much so that it first attracted the interest of Warp Graphics, its first publisher, and then of others up to Image Comics. In fact, the saga has not yet ended even if, after many periodic releases, Doran has announced that she wants to write an ending shortly.

Following the evolution of comics over the years, the growing attention to the study of the graphic construction of the table and the psychological and physical characterization of its characters is evident. Colleen Doran is talented and productive enough to drop out of school very early due to the sheer amount of commissions and deadlines involved.

In 1985, cartoonist Keith Giffen realizes her skills and introduces her to DC Comics and her first professional comics work. Among the titles to which he dedicates herself, Teen Titans and Wonder Woman. Almost immediately, Marvel Comics also notes her and entrusts her with several issues of important titles such as The Guardians of the Galaxy, The Silver Surfer, Captain America, Amazing Spider-Man, X-Men ... also works closely with Stan Lee for the marketing sector of Marvel: her personal acquaintance relationship will lead her to design in 2015 the celebratory volume Amazing Fantastic Incredible Stan Lee, written by Lee himself and Peter David.

Alongside the rich production on the most mainstream titles, there are her authorial works, in which one can indulge freely in his artistic research, even on the representation of the body.

Over the years she collaborated with some of the most important authors of the period, protagonists of the British Invasion which strongly influenced, from the mid-eighties and then into the nineties, the level and tone of mainstream superhero comics, science fiction, and American fantasy.

With Neil Gaiman, for example, she worked on Sandman, illustrating the cycles A Game of You and Dream Country. With Warren Ellis she worked on Transmetropolitan (in a one-shot collateral volume, I Hate It Here ) and above all on Orbiter .

Orbiter, released in 2003 with Vertigo, seems almost sewn by Ellis on the Doran stretch. The crew of a ten-year missing space shuttle suddenly reappears, but all members are catatonic and their journey holds some kind of mystery. In particular, part of the aircraft became organic. It is not strange that Ellis has chosen precisely the physicality of the unconventional characters of Colleen Doran, to make this component uncanny.

Doran is now in her forties. She and Emil Ferris are almost the same age and just at the age of forty the life of Ferris, already not easy, changes forever.

Emil Ferris as a child, forced into an orthopedic corset, entertains classmates in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago with her drawings. Daughter of two artists, Eleanor Spiess, symbolist painter, and Mike Ferris, designer and illustrator, Emil would like to follow in the footsteps of her father, who designs toys and even pinball machines. However, pinball machines are male territory and these commissions will remain closed to her. She has motor problems and the doctors offer her a painful future and a fairly short life. She, fond of monsters, of Filmland's Famous Monster magazine, of EC comics, wonders if the condition of a monster, in the sense of an outsider, of a person on the margins, is somehow close to her.

She also leaves school early, does tasks that allow her financial survival, and meanwhile continues to work as a freelance illustrator. Pregnant with a child at thirty-four, she never stops managing multiple jobs at the same time.

Exactly on the day of her 40th birthday, the banal bite of a mosquito transmits a potentially lethal disease, caused by the West Nile virus.

She wakes up after nearly a month in a coma, has a six-year-old daughter to care for, and paralysis in most of her body. The doctors throw what looks like yet another curse, she won't walk anymore. She does not give up and begins to draw what will be, fifteen years later, her debut graphic novel. She draws it with a ballpoint pen on a notebook and gets help from her daughter. She finishes college, a woman in a wheelchair in the midst of droves of twenty-year-olds full of hormones and life.

She makes drawing her physiotherapy. What she could no longer do, maintain control of his realistic hatching style, the son of classical and modern art studies and visits with her brother and parents to the Art Institute of Chicago, gradually returns to emerge on paper. It will take years to finish her first book and dozens of publishers will reject it, until she meets Fantagraphics Books.

My Favorite Thing is Monsters (in Italy: My favorite thing are the monsters , Bao Publishing, 2018) is the diary of the small Karen Reyes, ten-year-old girl from a multiethnic family, just like that of Ferris.

Little Karen is portrayed as a werewolf girl who, committed to living the life of the neighborhood, runs into a murder; her neighbor, a Holocaust survivor, is shot and killed and she decides to investigate. The book comes out with the same lined layout of his notebook and without the cage in the table, like a diary (the text is very rich) illustrated with drawings and comics. The influences on the style of Ferris are many and all deliberately recognizable and explicit: from Daumier to Goya, to get to the illustrated books (in particular the complete work by Dickens of the publisher Collier) and to her masters in the comic field, Art Spiegelman, Robert Crumb, Alison Bechdel.

A narrative thread unites her tormented life, the hand rehabilitated by the exercise (her outlined style is the result of a patient and hypnotic work) and the bodies she draws, characterized by bearing the signs of their history; in the book coexist embodied works of art, funerary statues that come to life, monsters that are grotesque and funny and truly monstrous and dangerous human beings.

For Ferris, the monster is the symbol of something that differs from the commonly accepted norm: a sick child first, then a girl attracted to other women and with a life on the fringes, the monster is the one she hopes to transform into in order not to have to define herself. necessarily in a precise way, to escape from a sick body, or even, kissed by a vampire, to become a body that overcomes death.

As Emil Ferris struggles to get her book published around 2015, Colleen Doran is teaming up with yet another sacred monster, Alan Moore. Emil tells the story of the wolf-girl, Colleen illustrates a webcomic experiment on a portal that Moore called Electricomics, works that will never be printed and born for the web.

Also in this case the story is about a child, one of the most famous of the protagonists of the comics, Little Nemo. In Moore and Doran's version, the delicate turn-of-the-century baby wakes up in the devastated and disenchanted body of the adult Big Nemo, who definitely no longer lives in Slumberland.

A good year goes by, and My Favorite Thing is Monsters has gone to press. Or rather, it was sent to print abroad because many publishing houses decentralize the work for large runs, to lower costs. While the freighter carrying the book run is crossing the Panama Canal, the Chinese transport company goes bankrupt and the freighter is seized for months. For those who have an emotional relationship with books, it is alienating to think how, in their physicality, they are goods, packages, packages, and boxes, and that they can be victims of accidents and upheavals. Like those who continue to haunt Ferris' life and whom she faces with an enviable willpower.

When it is finally published, the reception of the book is surprising (it will come out in two volumes, being about 700 pages): it wins two Ignatz Awards and three Eisner Awards; is nominated for a Hugo Award as "Best Graphic Story" in 2018, wins the Fauve D'Or at the Angoulême International Comics Festival, and the Gran Guinigi 2018 for the best graphic novel at Lucca Comics and Games. In recent news, Ferris has won a fellowship at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. They are all important and prestigious awards, but above all the success is with the public.

In 2019, Colleen Doran returns to collaborate with Neil Gaiman who, like Warren Ellis, appreciates his sign and his ability to adapt to stories: together they work on the reinterpretation of a timeless fairy tale, Snow White, which will be released with the title of Snow, Glass , Apples . The story starts from the stepmother's point of view.

To tell this immortal and classic story, Colleen Doran does a very thorough stylistic research on Harry Clarke, illustrator and glass engraver, active in Ireland between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Her style, reminiscent of that of a darker and more tragic Aubrey Beardsley, fascinates her very much and when she discovers that Neil Gaiman has an original, she runs to England to study it from life, especially in the use of color.

By a coincidence of fate, or because the tone of the story marries in both cases with this livid atmosphere, the result will be a color palette very similar to that of My Favorite Thing is Monsters.

As she has already done, and as Emil Ferris has also chosen in her book, Colleen Doran frees herself completely from the cage and chooses to mark the time of the story through the composition of the table; the bodies, the costumes, the environments become decorative details but at the service of the story.

The life of the two authors also meets on a point to be touched with a lot of respect, given that they themselves have decided to talk about it only partially; the issue of harassment.

Doran hinted at this during the early stages of the #MeToo movement, stating that she cannot talk about the situation she experienced as a young woman due to an NDA contract, a type of agreement that provides for the non-disclosure of certain confidential information. She hinted that she had experienced situations of abuse during a working relationship when she was young and still inexperienced. Emil Ferris recounted in more detail what happened to her as a child and the abuses by an acquaintance of relatives, but she still decided not to make it a central topic in the description of her artistic growth and in her biography.

Similarly, even if for Ferris this characteristic is much more evident, the idea of drawing as therapy ends up by combining their two sensibilities. It is Colleen Doran who speaks in these terms interviewed by The Comics Journal about the style she took from that of Harry Clarke, but she could not better tell what Emil Ferris herself describes:

“[After studying his working method], I wondered how much of that approach was meditative or therapeutic for him. That kind of work puts you in an incredible zen state. It sounds strange, but looking back on Clarke's health problems, I was wondering how much of that approach was a reaction to her infirmity. As a person with chronic health problems, I pay close attention to which arts activities consume you and which are invigorating. You spend hours every day on those little details and want to take your arm off. But in the end, it is hypnotic. I bet drawing those things made him feel better. It made me feel better. '

“It ain't me, babe”, a portrait of Trina Robbins by Valentina Griner https://www.fumettologica.it/2021/03/trina-robbins-fumetti/

Thursday 18 March 2021 at 18:00 for the cycle "Women in Comics" will be held the meeting "Comics and feminisms: and where were we?", Between Trina Robbins (from the USA) and Silvia Ziche (from Italy), moderated by Susanna Raule . Live on Zoom and on the ARF Facebook page and COMICON . The event anticipates the Women in Comics exhibition to be held in Rome.

It's a normal opening afternoon at De Young, one of San Francisco's two Museums of Fine Arts, and the usual California sun shines on the palm trees. Inside the galleries, there are visitors intent on admiring the permanent collection of American art. A distinguished lady, petite but with a kind smile and bright clothes, is staring at a painting by Robert Henri that portrays an elegant woman, with a white scarf to enhance the red color of her hair. Suddenly, the distinguished lady takes a pencil out of her bag and starts writing on the caption.

The museum guards rush in: «Madam, what are you doing! STOP! ». «I have no intention of touching the painting, God forbid», she replies, «but the caption needs updating. The name of the woman portrayed is not shown, nor her biography! ». We do not know if it was actually a sunny afternoon but the facts went like this, according to the story of Trina Robbins.

Trina Perlson was born in Brooklyn in the late thirties in a family context that she defines loving and serene. The surname Robbins is that of the ex-husband; years later he will find himself reflecting on the family surname, Perlson, arbitrarily attributed to his father by immigration officials on Ellis Island (to Americanize his parent's real surname, Perechudnik, a Belarusian migrant).

The knowledge of the marginalized condition (but more than anything else the perception of this condition) probably comes from her childhood, spent in a neighborhood inhabited by modest families of workers of Irish, Italian and German origin who did not look favorably on her family, decidedly progressive and of Jewish origin.

She has been drawing and reading comics from an early age, and can't stand when she hears that girls don't read them. She loves to copy authors who will influence her works; Matt Baker, one of the designers of the trend informally called "good girl", whose protagonists are always beautiful women; Wallace Wood and his science fiction. These are the years of Timely Comics publications and teen comics dedicated to girls like Patsy Walker, Katy Keene, and Love Romance.

The war years and the immediate postwar years had given impetus to publications designed for girls and sometimes made by women. In America (and in other countries) the departure of men for the front leaves room for women in the workplace and also makes them consumers, thanks to factory wages. At the time, little Trina certainly did not notice it, but many comics were not signed or in any case, the memory of the authors was lost. Years later, Robbins' historical research work will extend to this period as well.

Her adolescence, at the turn of the fifties and sixties, comes at a historical moment in which the ferment is felt in the air. She frequents the Village and Washington Square, dreams of Bohème and of moving to be an artist in Paris. France is a bit far, but interesting things happen on the West Coast too and Robbins moves to Los Angeles. She lives the hippie movement in a spontaneous and naïve way, like all the very young people who have taken part in it. The cultural and sexual revolution is a moment of great collective liberation which, however, presents fundamental contradictions. Disinhibition, welcomed by all, is experienced passively by some but above all by some: to say no, to withdraw from a relationship means to be ancient, repressed, reactionary. And beyond sexual liberation,

Trina Robbins returns to New York and takes over a space for her boutique, Broccoli. In the California period she learned to sew and create super colorful and psychedelic clothes, which she made for young and emerging artists; Donovan, Sonny and Cher, The Mamas and The Papas. She also knows Jim Morrison, obviously without knowing which rock legend she became friends with. Her career as a dressmaker and stylist doesn't seem to be much about her work as a cartoonist, yet years later it is Prada who gives her a surprising phone call.

Pop Art explodes in America. Comics, also thanks to this movement, attracts interest and gets consideration. When the phenomenon of the underground is born, the authors are determined to explore its full potential as an adult art form. Underground publications are alternative, self-produced, not necessarily of quality but free in content and above all far from the superhero and youth comics that represented most of the production. Trina Robbins, who went on to draw, is introduced to the East Village Other newspaper .

Time passes, the winter weather in New York is harsh, it is difficult to sell clothes in boutiques after Christmas and the California sun must be a good memory: Trina Robbins moves to San Francisco, leaving her shop and home to friends. She is not the only one to arrive more or less in those years. Robert Crumb arrived in 1967, determined to have, from that moment and forever, the most total artistic freedom as an author after years of work in the agency and for advertising. In 1968 he published and self-distributed (in a physical sense, by hand) the first issue of the historic magazine Zap Comix, considered the birth of the underground movement.

The environment of the comics leaves a bit of bitterness in Trina Robbins, who perceives the authors as part of a "male club" in which women have placed only as companions and stands at conventions (the first will be in the seventies). At parties, the friends of the tour present her as “the stylist”, she who has always drawn and would like to be an author.

With Crumb, she clashes directly: the problem is certainly not sex and nudes (the X used in the word Comix is borrowed from the X of porn films in the cinema), but the rapes and violence contained in the stories. Crumb explicitly declares that he wants to represent the most extreme sexual fantasies without filters and fully claims his freedom of expression. It does not want to be approved or censored, it does not want to be boring and repetitive, it wants to represent what is really in people's heads and insists on the argument that drawing perversions on paper is, if anything, a liberation of the libido. Robbins does not deny Crumb's art, which marked an era, but insists on his responsibility for legitimizing other men to find the most misogynistic attitudes funny.

Each week, Trina Robbins takes a bus from San Francisco to Berkeley to deliver her designs to The Berkeley Tribe. Universities were the forge of these productions and hosted collectives in search of new spaces for struggle and expression. At that time she reads her first feminist article, “Why the women are revolting”, from The Berkeley Barb. It is like a bolt of lightning for her, who perceives the very sense of belonging she was looking for.

He enthusiastically contacts the women's liberation magazine It Ain't Me Babe, meets the women of the editorial staff, and begins her first militant collaboration, designing covers, comics, and illustrations for them. We are always talking about self-produced magazines, paginated and printed in an economic way, distributed by hand or in small shops, obviously without a budget for the authors, which however hosted the ferment and enthusiasm of a generation.

Not long after, Trina Robbins is ready to produce her first full comic book, all designed by women. In San Francisco, she knows only one other full-time cartoonist, Barbara “Willy” Mendes, but together they find others: Nancy Kalish, Lisa Lyons, Meredith Kurtzman, Michele Brand. It Ain’t Me Babe Comix (1970) is born, paying homage in the name of the magazine, even if the drawing is not the same.

Shortly after, in another city in California, the Tits & Clits series by Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevely, two lesbian authors who draw in collaboration with other designers, was published, demonstrating the generalized desire to express themselves with a collective voice. It Ain’t Me Babe Comix should be given the time record.

By 1972 the collective had accumulated enough experience to devote itself to a new comic that cyclically collected works by other authors, with a “rotating” editorial team to ensure that there was no hierarchy within the collective and that all had equal decision-making power. Robbins also finds a publisher, who will pay her an insane $ 1,000 for the publication (Ron Turner of Last Gasp Publishing).

The name of the new collection is already written in the heads of the girls who continue to refer to it as "the cartoon of women". Thus was born the first issue of Wimmen's Comix. Already groundbreaking in itself, the collection contains the first comic to tell the story of a lesbian girl, “Sandy Comes Out,” drawn by Trina Robbins and based on the life of Crumb's sister, her roommate. Trina is once again not aware of the primacy, she just wants to draw the reality she sees around her.

Thanks to Wimmen's Comix, many authors make their debut in comics, whatever their style and genre or even their actual talent; the key thing is to give them freedom of expression. Among others, Lora Fountain with "A Teenage Abortion", Sharon Rudahl with the psychedelic "Tales of Sativa," Alison Bechdel, and Melinda Gebbie. Aline Kominsky and Diane Noomin will also draw on Wimmen's Comix to leave it, to put it mildly, after personal and artistic differences (Aline will become Crumb's partner, and with Noomin she will found another collection).

The publication goes on sporadically for years, going through the crisis of the underground press. A new distribution system and the death of small independent bookstores, the main resellers of the alternative press, causes a sharp decline in publications.

To give an idea of the situation, in 1973 a women's magazine refused to sell an advertising page in Wimmen's Comix. A Supreme Court ruling had stated that each city could decide for itself which publications were obscene; thus a generalized fear had spread of running into complaints for having advertised or published materials locally considered pornographic.

Distributors and retailers used to say that there was no more space and audience for magazines like these, also because women didn't read comics. An old prejudice that tormented Trina Robbins, who knew well that women read, were authors and existed as an audience and as producers of valuable content, even if historically many magazines had no archives, did not put the names of authors and a lot of information on female authors they had been lost.

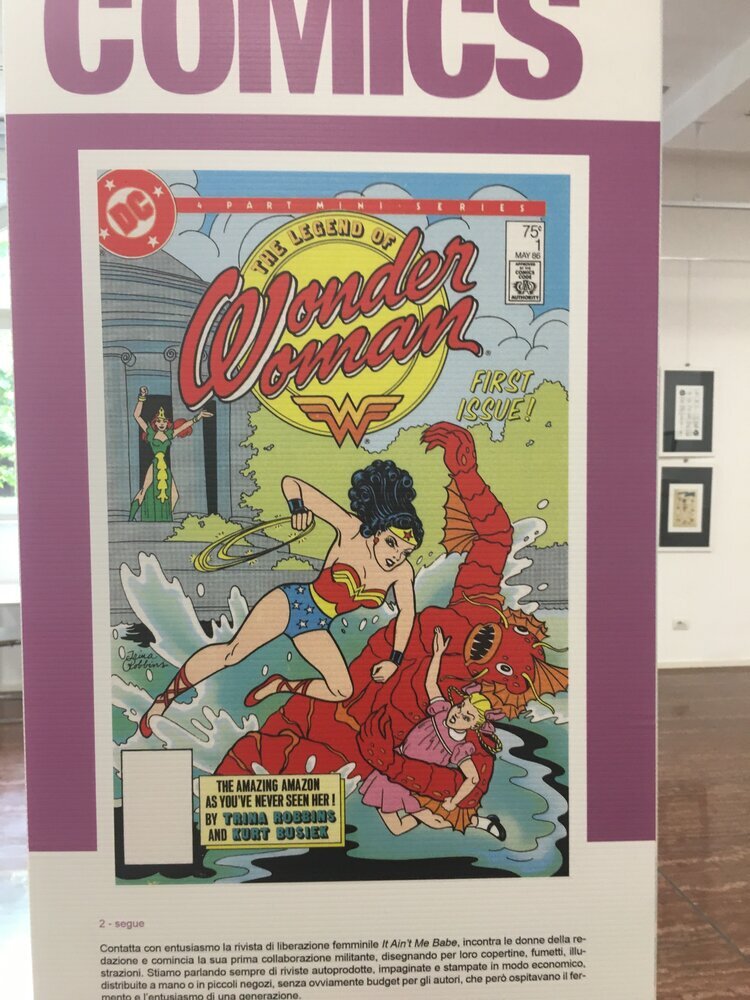

Trina Robbins' artistic activity continues and in 1985, the first woman in history, she draws a cycle of Wonder Woman stories for DC Comics ( The Legend of Wonder Woman, in 4 albums). What engages and fascinates her the most, however, is her mission, to restore memory to other women artists in the world of comics.

In 1983 he wrote Women and the Comics with Catherine Yronwode, then A century of women cartoonists, published with Kitchen Sink in 1993; From Girls to Grrrrlz: a History of women's comics from teens to Zines, with Chronicle Books in 1999, which retraces the underground movement; Pretty In Ink: North American Women Cartoonists 1896–2013 with Fantagraphics Books in 2013; Flapper Queens: Women Cartoonists of the Jazz Age, with Fantagraphics Books in 2020.

She will also take care of promoting the work of other cartoonists, and obviously she will dedicate exhibitions and conferences to their work, also thanks to the huge collection accumulated in her years of activism and dissemination and to a personal commitment that has never failed. Her latest book is dedicated to rediscovering the designers of the Flapper Era , that era of great costume revolution in the 1920s.

A few names among the many authors she contributed to discover and rediscover: Ethel Hays, Gladys Parker, Virginia Krausmann, Martha Orr, Tarpé Mills, Lily Renee, Fran Hopper, Jill Elgin, Hilda Terry, Ramona Fradon, Elizabeth Berube, Barbara "Willy ”Mendes, Marty Links, and Marie Severin.

Meanwhile, at the De Young Museum, it is yet another afternoon illuminated by the usual California sun, and several visitors walk through its rooms. Some stop in front of the picture of a beautiful and elegant red-haired woman. The caption today contains the following information: “Robert Henri,“ O. in black with scarf (Marjorie Organ Henri) ”. The woman in the portrait, Henri's wife and model, was a draftsman and cartoonist for the New York Journal in the 10's.